The believers are having a hard time standing tall.

There are a couple dozen of them and they've been on their feet for more than an hour, holding up sheets of paper that say things like WE STAND TO ESTABLISH JUSTICE AS A MORAL ISSUE or PREACH GOOD NEWS TO THE POOR. Now they're bracing their elbows against their sides. The message is getting heavy.

It's midmorning on New Year's Eve—not quite eight weeks since Donald Trump was elected president, not quite three weeks before he takes office—and the believers have come from all over the country to resist. They've gathered here in Washington at National City Christian Church, where Lyndon Johnson worshipped; his favorite spot, six rows back, was named the president's pew. Today the church is hosting a teach-in so activists can learn the best ways to protest back home. Part of the price of entry, it turns out, is participating in a well-crafted photo op, holding up the signs at the press conference that kicks off the event. The believers and their signs create a frame around the man in the middle, a preacher from North Carolina named the Reverend William Barber II. He is the main reason they came.

During the press conference, while others take their turns at the pulpit, Barber leans back on a wooden barstool. At fifty-three, he has a severe arthritic condition in his spine and bursitis in his left knee. It hurts to sit and it hurts to stand. When he's bent over in the background and propped against his stool, it's hard to see the man Cornel West described as "the closest person we have to Martin Luther King Jr. in our midst."

But now he rises up toward the microphone, and the believers stand straighter.

Barber's ecumenical activist group, Repairers of the Breach, has crafted a letter to Trump asking to talk to him about voting rights and poverty and justice and health care. They're not going to Mar-a-Lago. They want him to come to church.

"We know by scriptural tradition that even Moses talked to Pharaoh," Barber tells the believers. "That Elijah talked to Ahab. That Jesus challenged the powers of their day. Dr. King met with Johnson, who had been a former segregationist. And he didn't always get what he wanted. But he served notice."

The believers have come to the teach-in because Barber served notice in North Carolina. Since 2013, he has led a series of rallies in Raleigh that have come to be known as Moral Mondays. From the beginning, they challenged the state's Republican-dominated legislature and its Republican governor, Pat McCrory. That first year, more than nine hundred protesters, including Barber himself, were arrested for filling the legislative building and refusing to leave. They persisted. Voters paid attention. Moral Mondays helped defeat McCrory in last year's election, even as the state turned red in the presidential race. Barber spent 2016 traveling to twenty-two states to build similar movements around the country. But as he worked to battle the Pat McCrorys at the state level, the nation produced a much bigger opponent. And now the question is whether Barber can make his voice strong enough—and his movement large enough—to take on President Trump.

The opposition to Trump so far has been powerful but leaderless—millions of bodies but not many faces. But Barber is working his way toward the middle of the frame. He's a regular on MSNBC and on Roland Martin's show on TV One. He has a PR advance team and a video crew to livestream his sermons. He has traveled to New Jersey to speak to union workers and to a church in Flint to preach about the water crisis there. He helped lead a march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, on the anniversary of the "Bloody Sunday" march of 1965. He went back to Raleigh for a civil-rights rally that drew tens of thousands of people. And the day before the House was supposed to vote on a health-care plan that would cut benefits for millions, Barber led a group of clergy and activists to the Capitol to protest. One by one, they placed a pile of holy books outside Paul Ryan's office. People talk about swearing on a stack of Bibles, but it's not often someone is confronted with a literal stack of Bibles. Ryan later pulled the plan from the floor before it came to a vote. Maybe the Lord really does work in mysterious ways.

But back at the Washington teach-in on New Year's Eve, Barber is wearing his followers out. Just when it looks like the press conference is over, he comes back around to take questions. He had told the people holding signs not to lock their knees. Some didn't listen. A couple of them sway like pines in the wind. One woman drops her sign and heads for a side door, looking queasy. Barber keeps talking. Surely he is hurting, too. But he has one last point to make.

"You never march without a map," he says. "You don't just start protesting. You don't just start having civil disobedience. You have to have a map. What is it? What is the moral imperative and the moral direction, and what is the moral imagination?

"The teach-ins are going to be happening across the nation, because the teach-ins are designed to build a movement. … This is serious business. And we are serious people. God bless you."

The camera shuts off. The believers drop their arms and bend their knees. Barber smiles. "That was good," he says. "Thank you for holding on."

The spotlight landed on him last July at the Democratic National Convention. Barber spoke on the final day, one in a string of opening acts before Hillary Clinton accepted the nomination. He's a big man—six foot two, built like an old nose tackle—but nobody paid him much mind when he limped onto the stage. He had ten minutes. By the end, everybody in the building—and in the TV audience—was paying attention. His speech spawned a thousand blog posts and YouTube clips.

Toward the end, with the crowd already on its feet, he thundered:

They tell me that when the heart is in danger, somebody has to call an emergency code. And somebody with a good heart will bring a defibrillator to work on the bad heart. Because it is possible to shock a bad heart and revive the pulse.

In this season, when some want to harden and stop the heart of our democracy, we are being called like our foremothers and -fathers to be the moral defibrillator of our time.

We must shock this nation with the power of love! We must shock this nation with the power of mercy! We must shock this nation and fight for justice for all! We can't give up on the heart of our democracy, not now, not ever!

The headline in The Washington Post read, "The Rev. William Barber dropped the mic."

It wasn't hard, in that moment when it felt like Clinton would cruise into the White House, to visualize Barber owning the unofficial title of America's preacher—the spiritual advisor to those given the earthly task of running the government. On election night, he checked into a suite at the Sheraton in Raleigh, along with a few of the people closest to him, to watch the results. North Carolina Democrats had rented the convention center one block down, expecting to celebrate.

The hotel suite got real quiet at about nine that night.

"When you have the DNA of Native American people and black people and white, like I do in my bloodline, and you think about all that history, you understand that elections can be strange creatures," he says later. "And voting doesn't always happen around what is right and what is moral."

He hadn't planned to party with the Democrats anyway. He endorsed Clinton at the convention, but he's a registered independent and calls himself "a theologically conservative liberal evangelical Biblicist." His policy positions fall far to the left on today's political scale. But he sees most of them as coming from conservative traditions rooted in the Bible—traditions that don't line up with conservative politics today.

People who focus their moral energy on gay marriage and prayer in schools, he says, are missing what Jesus cared about the most: justice and mercy. It's a stock line in his sermons: "They are saying so much about what God says so little, and so little about what God says so much."

"I come from a Bible-thumping family," he said during a November sermon at Myers Park Baptist Church in Charlotte. "We couldn't even eat chicken until we quoted Scripture. I can't find anything in the book that says your major concern ought to be tax cuts for the wealthy and giving money to private schools and making sure people have gun rights. But I can find in Deuteronomy that you're supposed to care for the stranger and the poor."

Barber was born in Indianapolis in 1963, two days after the March on Washington—it's a family joke that he waited to come out until the march was over. From the start, he was steeped in civil rights. When he was four, his family moved to eastern North Carolina, where his father grew up, to integrate the faculty and staff of the schools in Washington County. William Barber Sr.—people called him Doc—taught science and preached in Disciples of Christ churches. Barber's mother, Eleanor, was a secretary. Barber was five when Martin Luther King was assassinated in Memphis; he didn't understand what had happened, but he remembers his mother screaming at their black-and-white TV and his father coming home in tears. Barber started school in a segregated kindergarten and became the first solo black student-body president at Plymouth High School—before he won, the school had separate white and black presidents. He enrolled at North Carolina Central, a historically black university in Durham, to study politics and prep for law school. He planned to be a civil-rights lawyer.

Brian Kennedy was in the Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity with Barber at NCCU. He remembers his friend—who went by Billy back then—leading a student march to Raleigh to demand more funding for historically black colleges. "The thing that stood out to me was that a student was doing these protests," Kennedy says. "Everybody wanted to make a difference. He was the only one I knew who was actually making a difference."

Barber never meant to preach. Ministers go back hundreds of years on both sides of his family. He wanted to cut his own path. Besides, to him church felt like a way station—a place to get married or buried, but not a place to change the world. He had seen how churches had turned away his father when Doc Barber's sermons veered toward politics and justice.

But he could not escape a sense that his faith was linked to his goals. He thought of a verse from Micah, the Old Testament prophet: What does the Lord require of you but to do justice, and to love kindness, and to walk humbly with your God?

And he thought of the way his dad phrased the same idea: There's no separation between justice and Jesus. He thought about what he calls "the great river of resisters," people who used their faith to challenge the rulers of the day, from MLK to Harriet Tubman to John the Baptist and Jesus himself. His family had immersed itself in that river, too. He realized he could no longer stay dry.

One day he called home from college.

"Dad, I need to talk to you," Barber said.

"I know," his father said.

Back home, they took a long ride in his dad's old truck, talking about what it means to get the call. Barber went back to NCCU and finished his degree in public administration. Then he went to Duke for divinity school.

His first pastoral job, in 1989, was in Martinsville, Virginia, a town best known for its NASCAR track. Barber was so nervous before his first sermon that he forgot his dress shoes; he preached in sneakers. Before long, he met some workers at a local textile mill who wanted to start a union. He supported their fight, but the mill bosses were powerful in Martinsville, which was once called "the sweatshirt capital of the world." The union vote failed.

As Barber tried to figure out what went wrong, he realized he had spent most of his time with black workers and black clergy. He hadn't reached out to the poor white workers and their pastors. It got him thinking about intersectionality—the idea that every person's identities (gender, race, class, etc.) overlap and can't be separated out. And that got him thinking about the Fusion Party movement of the late 1800s, in which black and white politicians from different political parties joined forces to reach common goals. One of the biggest Fusion Party factions had been in North Carolina. Barber's father wrote his master's thesis about it.

That idea led Barber to his own type of fusion, one that he connected to the civil-rights era and his biblical beliefs. He set out to highlight the overlapping needs and desires of white people and black people in poverty, of people fighting for fair housing and people fighting for LGBTQ rights, of Christians and Muslims and Jews. All of those people are likely to disagree on a lot of things. But if they can find places to work together, he says, they can do something powerful.

Like, maybe, spoil the plans of the new president.

At the Washington teach-in, Barber lets others take the lead. There's a session on voting rights, one on health care, one on the costs of war. Karenna Gore, daughter of Al and Tipper, helps run a session on climate change. Almost every speaker provides charts and stats and handouts for the audience of 200 or so to take home. "This could be the fight of our lives the next few years," says Keith Kessler, a Washington activist, who showed up wearing a yarmulke and has spent the whole morning being mistaken for a rabbi. "We have to be ready."

Barber dips in and out, firing up the crowd when too many PowerPoint slides leave them glassy-eyed. Midway through the conference, he steps into a side room to talk to me. Joe Ward, his assistant, brings Barber his stool. Somehow none of us can find the light switch. So Barber leans against the wall in the dark, his preacher's voice gone, talking calmly and slowly about the connection between his life and his beliefs.

His spinal condition is called ankylosing spondylitis—it's a rare form of arthritis that basically fuses the vertebrae together. He found out he had it in 1993 when he woke up one morning and couldn't move. He had just accepted a job as pastor at Greenleaf Christian Church in Goldsboro, a town southeast of Raleigh known mostly for its barbecue. Barber spent three months in the hospital and used a walker for twelve years after that. He dieted and swam and meditated and prayed, hoping to get better. Late one night in 2005, he got out of bed to pee and realized he hadn't used the walker to get to the bathroom. That morning he went down the street and bought a cane. It's been beaten half to death now. Almost all of the white paint has chipped off. Friends keep offering to buy him a new one. He keeps the one he's got, as a reminder.

Barber is still the pastor at Greenleaf, twenty-four years later. He and his wife, Rebecca, have five children. Twenty years ago, their year-and-a-half-old daughter was diagnosed with hydrocephalus, or fluid on the brain. She had surgery at Johns Hopkins. The surgery was a success, and she recently graduated from North Carolina Central with degrees in English and history. (The neurosurgeon, by the way, was one of the finest in the world and not known for much else back then. You might have heard of him: Ben Carson.)

Barber rarely talks about his kids—he gets death threats because of the work he does, and he doesn't want them exposed. He mentions his daughter to point out how important health insurance has been to his family. Without it, there's no way they could have paid for his arthritis treatment or her brain surgery, much less both. Barber favors universal health care—he thinks President Obama fell short, even with the Affordable Care Act—and he sees health care in general as one of those fusion points. Poor people of all backgrounds face high doctor bills or skimp on medicine they can't afford. Maybe it's an issue to build a movement around.

Barber also sees health care with a pastor's eye: "I have to bury folk who die because politicians block them from having health care that the politicians have."

As you might imagine, a lot of those politicians and their allies are not fond of Barber. Pat McCrory dismissed the Moral Monday protesters as "outsiders," although nearly everyone arrested in the protests was from North Carolina. Thom Goolsby, a Republican state senator, called the protests "Moron Mondays." Sean Hannity spent an eight-minute segment on Fox News in 2014 calling for the NAACP to denounce Barber (who has been president of the North Carolina chapter of the organization since 2005) for saying that conservatives "frantically seek out people of color to become mouthpieces for their particular agenda."

Last spring, Barber got into it with two men seated behind him on an American Airlines flight from Washington to Raleigh. He says they had been drinking and were verbally abusing him. Barber got up and turned around to respond before sitting back down. Eventually, a police officer boarded the plane and kicked Barber off the flight. He filed a lawsuit against American in December, saying he was removed because of his race.

Barber is a large black man in a world that does not always know how to deal with that. He's a Christian in a world where that doesn't always mean what he thinks it should mean. He has been on the inside, or close to it—the stage of a national political convention is deeper inside than most of us ever get. But he always sees himself out on the edge. His family moved south to help integrate schools. He wore knockoff Chuck Taylors because he was too poor for the real ones. His body is a wreck and his baby daughter almost died. He can afford a hotel suite. But his mind is out there with the bankrupt and broken.

Three years ago, Barber was a guest on Bill Maher's HBO show, Real Time. He leaned on his barstool, towering over Star Trek's George Takei. Near the end, the conversation turned to atheism. "I'm an atheist, too," Barber said, as Maher did a double take. "When it comes to those folks that say that Jesus is on the side of bigots and on the side of those that hurt people. That kind of God? I don't know him, either."

Here's the hard part.

Poor white voters, by and large, identify with Trump more than they identify with poor black people, much less poor immigrants. One: He's white. Two: He has promised to bring back factory jobs, even though he has revealed no plan that might actually make that happen. Three is that sweet-sounding promise to make America great again—again being the key word there. It means winding back the clock, and the further the clock winds back, the better it gets for white people in America.

And here's another hard part, maybe the hardest of all: You might get people to show up for one march, but not many will show up for ten—not to mention all the work in between. "This is the real challenge," says Bishop Tonyia Rawls, a Charlotte pastor who speaks with Barber around the country. "It's easy to get people fired up once. But once never gets the job done."

In almost every sermon, Barber will mention some young activist he's met who is ready to quit after one rally because nothing changed. He then reminds everyone that the Montgomery bus boycott—sparked by Rosa Parks refusing to give up her seat in December of 1955—lasted 381 days. Moral Mondays had no effect at first. But when people kept showing up, legislators fought back—or latched on.

Because of Moral Mondays, Barber knows he and his colleagues can build something sustainable. What he doesn't know yet is if it will scale into something big enough to matter.

We're in that little side room outside the teach-in, talking in the dark. Barber talks about being fifty-three and knowing it's likely that he's on the back half of his life. He preaches patience. But he feels time pressing in.

"So we know we're in a moral crisis," he says. "And it demands a moral revolution of values. And so it's got to be long-term and steadfast. And what we learned in the Moral Monday movement is, if you shape—if you can transform the consciousness of the people and connect it to an agenda and help people stop seeing their victories as just being what happens in the election. Instead, the victory is when you elect to stand up."

It is New Year's Eve night and the resistance has swapped churches. The crowd is bigger now, maybe five hundred people, and it has moved a couple of blocks to Metropolitan African Methodist Episcopal Church. Black Washingtonians have worshipped here since 1886. The church held the funeral for Frederick Douglass, who—despite what you might have heard in February—died in 1895. Tonight Barber is leading a watch-night service. Late services on New Year's Eve date back at least as far as the Moravians in the 1700s, but in many black churches watch night is linked to the night before President Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863.

The service starts at 9:45. There are so many speakers they take up the whole first pew. There are videos and hymns. It is nearly midnight when Barber lumbers to the pulpit for his sermon. He is dressed in black. His bent back forces his head down and his eyes up. He looks like a sly uncle about to tell you a secret.

"Long before any Russian hack, the American electoral process was compromised by racism and fear," he says. "This is nothing unprecedented in the American experience."

He starts to tell the Bible story of Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego, the three Jewish boys who refused to bow to the golden statue of Nebuchadnezzar, the Babylonian king. He can't resist the old black preacher's line of calling the boys Shadrach, Meshach, and "a bad Negro." It's a mixed crowd. Some of the white people aren't sure whether to laugh until they see Barber smile.

"They were dealing with this king who was a narcissist," Barber says, and the worshippers start to stand, knowing where he's going. "And he believed his own press reports. And they tell me he loved to build towers. And nobody had ever seen a tower like Nebuchadnezzar's tower. And he loved to cover his things, his towers, in gold. And he loved to make them shine. And he loved to build them tall and have meetings in the tower. And he loved people to bow down and worship at the towers."

The organist off to the side adding little exclamation points after every line.

"Nebuchadnezzar told these Hebrew boys that if they didn't bow down he'd throw them in the fire. [!] But what he didn't know is that those boys had a fire in them already. [!] Those boys had refused to eat the king's meat. Or the king's wine at Mar-a-Lago—I mean, at Babylon."

The crowd laughing with him now, people rocking in the pews.

"And they didn't believe the press. They didn't believe the tweets that the king kept putting out. While he was tweeting, they were singing the songs of Zion. And they were renewing their spirits. And the king and his men didn't know it, but Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego, they were a part of a moral movement. Because every age has a moral movement. And they didn't stand down. And because they didn't, they changed the king. They changed the climate. They changed the consciousness. They changed the fire. Because when they went in, the fire was seven times hotter. But when they came out, the Bible says they didn't even have the smell of smoke on them."

Everybody shouting.

"They brought about a moral revolution. Because they would not stand down. And I stopped by, January 1, 2017, to say that I believe in the power of a moral movement. I believe that standing down is not an option."

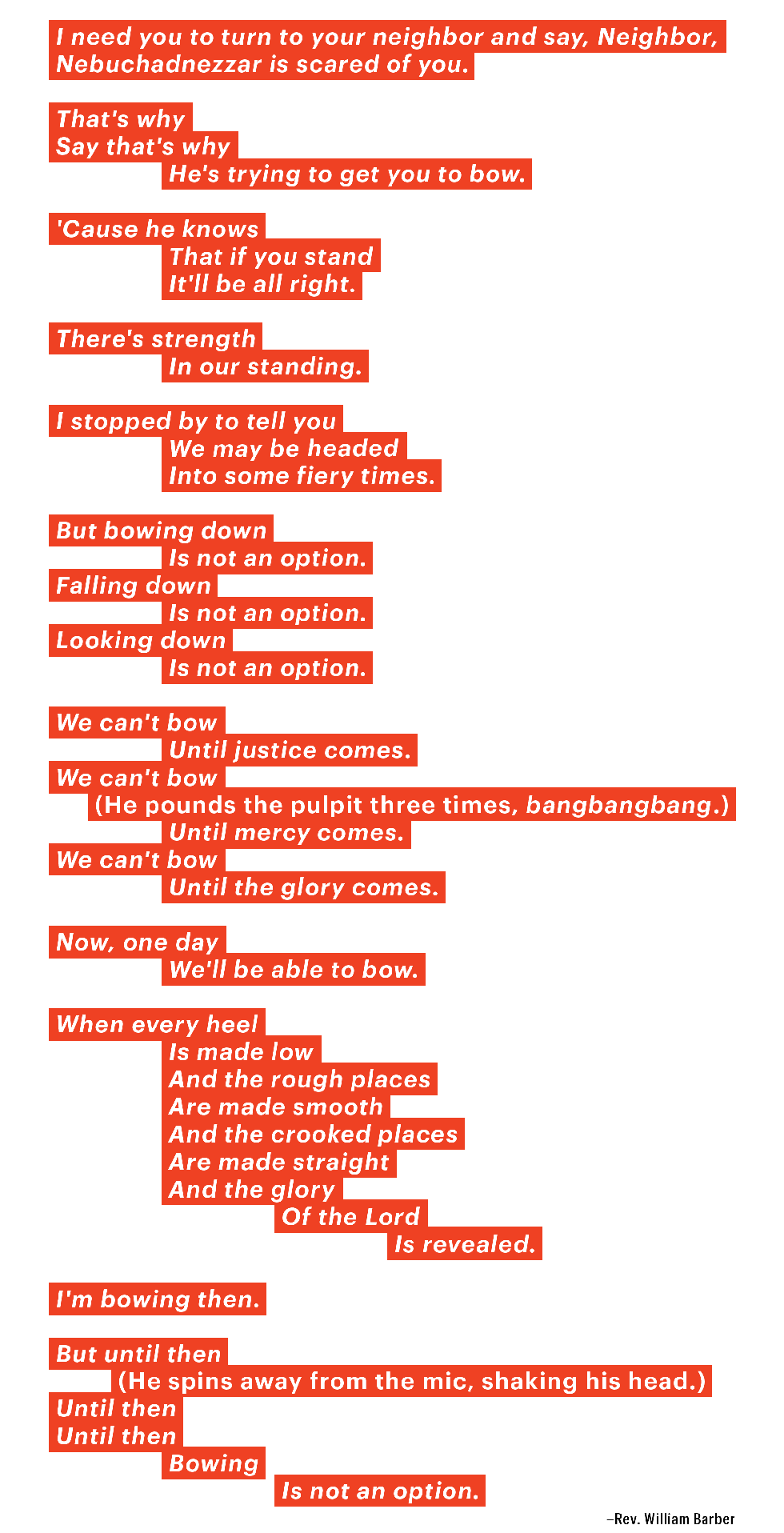

It's past midnight now, we are in the new year, and Barber shifts from long sentences into fragments. In the sound and the sweat, his sermon turns into a poem.

Barber walks off, and the old church creaks on its footings. The crowd is vibrating. It is clearly time for the doors to open and everybody to spill out into the street, hallelujah, but we are not done yet. Whatever comes now is destined to be an anticlimax. It turns out to be a video featuring, of all people, Joan Baez, singing, of all things, "Swing Low, Sweet Chariot." It also turns out to be a nice bit of cover. Because as Baez sings, William Barber escapes.

He has delivered the crowd into New Year's Day. But this particular New Year's Day falls on a Sunday. Barber has a congregation back home, and he owes them a sermon in a few hours. So he slides out the back without saying goodbye. When he leaves, the believers are still standing.

Tommy Tomlinson is the author of The Elephant in the Room, a memoir about being overweight in America. He’s the host of the podcast SouthBound in partnership with WFAE, Charlotte’s NPR station. He has written for publications including Esquire, ESPN the Magazine, Sports Illustrated, Forbes, Garden & Gun, and many others. He spent twenty-three years as a reporter and local columnist for the Charlotte Observer, where he was a finalist for the 2005 Pulitzer Prize in commentary. His stories have been chosen twice for the Best American Sports Writing series (2012 and 2015) and he also appears in the anthology America’s Best Newspaper Writing. He teaches magazine writing at Wake Forest University and has taught at colleges, workshops, and conferences across the country. He also has a Substack called The Writing Shed. Tommy and his wife, Alix Felsing, live in Charlotte with Alix’s mom and a cat.