A congressman paid tribute to him, the county school system dedicated a library in his name and a state university awarded him an honorary degree, calling him a source of inspiration and emulation.

Bill Murdock has led Eblen Charities, one of western North Carolina’s largest nonprofits, for nearly three decades, cultivating a reputation as a humble servant to the poor and a disciple of Mother Teresa.

But a CNN investigation into his background paints a different picture. Murdock was charged with a felony sex crime with a child in 1988 and pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor in a deal that one prosecutor initially involved in the case now considers an injustice. And he earned prestige with a resume built on exaggerated and dubious achievements.

One award that has burnished his image, the Mother Teresa Prize for Global Peace and Leadership, sounds impressive but came from a company he incorporated out of his home. He claims an educational background from some of the country’s most prestigious universities – Harvard and Stanford, where his attendance consisted of one-week courses in nonprofit management.

A familiar face in Asheville, frequently appearing in the local media, Murdock, 63, has risen to prominence in this tourist mecca nestled in the Blue Ridge Mountains while his criminal record has remained largely unknown.

When his conviction has surfaced, as it did last year after the University of North Carolina at Asheville chose him for an honorary degree and to be its commencement speaker, Murdock offered this explanation: A woman came on to him, he rebuffed her and she retaliated by falsely accusing him of sexual misconduct with her teenage daughter.

That account satisfied the UNCA Board of Trustees at the time. It also has satisfied the Eblen Charities board and an influential group of Asheville powerbrokers.

But CNN tracked down the victim from that case, who has silently watched Murdock’s stature grow. The Murdock she knew was her eighth-grade teacher, the 30-year-old married man who she says rubbed his body against hers, promised a future together and sexually abused her throughout her freshman year in high school.

“He would go into very elaborate stories about our dating, our wedding, and he always played himself as the hero,” said Shelley Love Baldwin, now 47. “My family was struggling financially. I was struggling. I just felt like he targeted us…. He saw vulnerability, and he swept in.”

The abuse left Baldwin suicidal and in therapy much of her adult life, she said, and traumatized her entire family.

“It’s been painful for years, and it just comes in waves of emotion for all of us,” said her brother, Scott Love, a pediatrician in Asheville. “And my family, I think we’ve all learned how to deal with it in some ways and never learned how to deal with it in others.”

Murdock maintains his innocence and denies ever abusing Baldwin. He said he became close to the Loves while separated from his first wife and that the family was unhappy when the couple reunited.

Murdock gave a 90-minute interview to CNN and refuted the allegations of the victim and her family. “There’s a whole lot more to this,” he said. “I don’t mind telling you the whole story….I just want to make sure I’m doing it the correct way.” Murdock said he needed to consult his lawyer first but never explained further, despite reporters’ follow-up phone calls and another visit to his office. The lawyer who Murdock mentioned told CNN he did not represent him. He referred questions to Murdock’s defense attorney from the 1988 case, who did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

CNN interviewed Baldwin’s parents, a former classmate and two medical professionals who said Baldwin told them years ago that she was sexually abused by Murdock. In addition, her siblings and a couple who worshipped with the family said they witnessed interactions between Shelley and her teacher that concerned them. Murdock himself admitted to an inappropriate emotional relationship with the girl in an audiotaped confrontation surreptitiously recorded by her father in 1988.

After learning the details of CNN’s investigation, the UNCA Board of Trustees rescinded Murdock’s honorary degree on March 8, citing questions about his background, awards and academic credentials.

Other organizations affiliated with Murdock refused to answer questions, including the Buncombe County schools. The same school district that accepted Murdock’s resignation the day before his arrest nominated him to a community college board in 2016 and named a school media center in his honor in 2018.

Many in Asheville see Murdock as the head of a charity that helps the destitute, a man whose awards and accolades are testimony to his character. How could he be capable of abusing a child?

“This is a cautionary tale about how we deny our suspicions and how we don’t listen to victims and how we’re willing to look at the good someone has done when they have done very bad things in their past,” said Wiley Cash, a New York Times best-selling author and writer-in-residence at UNCA.

But attitudes are changing. Decades-old accounts of sexual abuse are being re-examined in many cases.

More than 30 years after a young girl said she fell prey to her teacher, Baldwin, like many victims, is speaking out publicly for the first time.

Her abuse – and his denial

In an exclusive interview with CNN, Baldwin, her parents and siblings recounted what the family described as calculated grooming and sexual abuse by a teacher they trusted. Reporters shared those details with Murdock, who acknowledged a closeness with the family but provided a different recollection of events.

This is the Loves’ account:

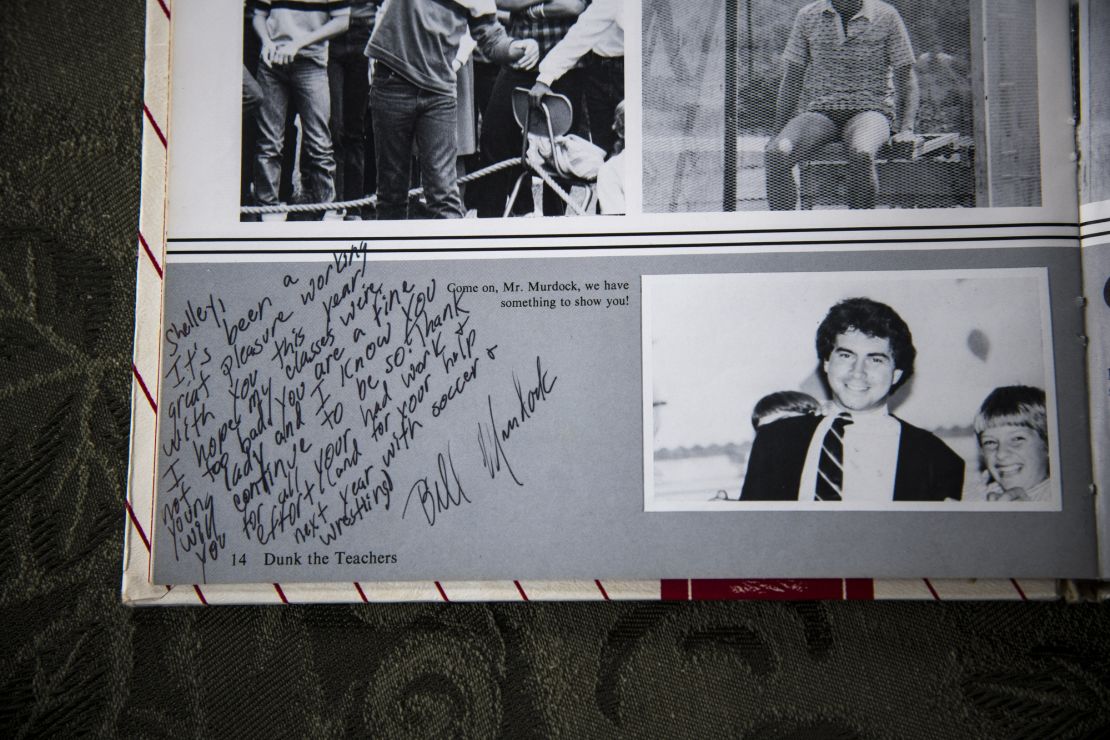

Shelley was a shy, bookish eighth grader in 1985. Placed in the gifted program at Clyde A. Erwin Middle School, she felt excited to learn Bill Murdock would be her math and science teacher. A gregarious guy and chummy with students, Murdock was popular. He kept her after class, working on math problems.

“The uncomfortable stuff started pretty early on with him bringing me to his desk,” she recalled. “His whole leg would be against my leg. His whole upper body would be against my body. [I’d] feel his breath on [my] face. I mean, he would just be all over me right there.”

During P.E., as Murdock played sports with the boys, Shelley said, he gave her his jacket, watch, college ring and tie to wear. It was kind of flattering, she recalled. It was also mortifying.

“I already felt awkward. I spent most of my middle school years trying to be invisible and not get attention. I just remember just wanting to melt away into the bleachers.”

One evening, the eighth-grader told her mom, “I think Mr. Murdock likes me.”

Carolyn Love remembers that moment and wishes now that she’d responded differently.

It’s probably okay, she said.

The touching continued throughout the school year, Shelley said, including holding her hand just moments before her mother was to pick her up. She felt trapped, pressured and confused. She was relieved when middle school ended. Erwin High School would be her escape, she thought – until she learned Murdock had taken a teaching job there.

Just before freshman year began, Carolyn said, Murdock showed up at the Loves’ home while she was working in the yard. He told her he liked teaching Shelley and could help their introverted daughter. He was going to coach soccer at Erwin High and suggested to Carolyn that Shelley become the team statistician.

Carolyn appreciated his gesture and encouraged her daughter.

“I thought, ‘Won’t that be good?’ with the kids, ‘cause she was shy,” she remembered. “You could see that she was unhappy…Bill was saying, ‘I will look after her.’”

Murdock and Shelley spent a lot of time together. “All the kids seemed to know or think we had this relationship, which was humiliating.”

At a home football game one evening, girls began to taunt Shelley about him. Crying, she took off, walking fast toward home.

Murdock drove up alongside her, offered her a ride. She got in. They drove, then stopped at an intersection.

“He reached over, and he grabbed my hand, interlaced his fingers,” she recounted. “He’s like, ‘I want to pray with you….’ He tells me how special I am.”

Then, she said, Murdock kissed her forehead. “He kissed my cheek, kissed my ear, started kissing, like, all over my face.”

Shelley shook her head, trying to back away but their lips made contact. “He said, ‘Well, you kissed me.’ That was his thing forever after that….’You kissed me.’”

When he stopped, Shelley slid back into her seat. Carolyn remembers Murdock explaining that he drove her daughter home because she was getting picked on at the game.

Carolyn and Doug Love sometimes worked past the time that Shelley and her younger siblings Heather and Scott arrived home from school. Carolyn had a job at a department store. Doug, a pastor, was working full-time at the Red Cross and trying to start a church.

They were raising their kids in a time before the sex offender registry, when Asheville was a small town and seemed like a safe place for children. Their faith was at the center of their lives. They saw the good in people.

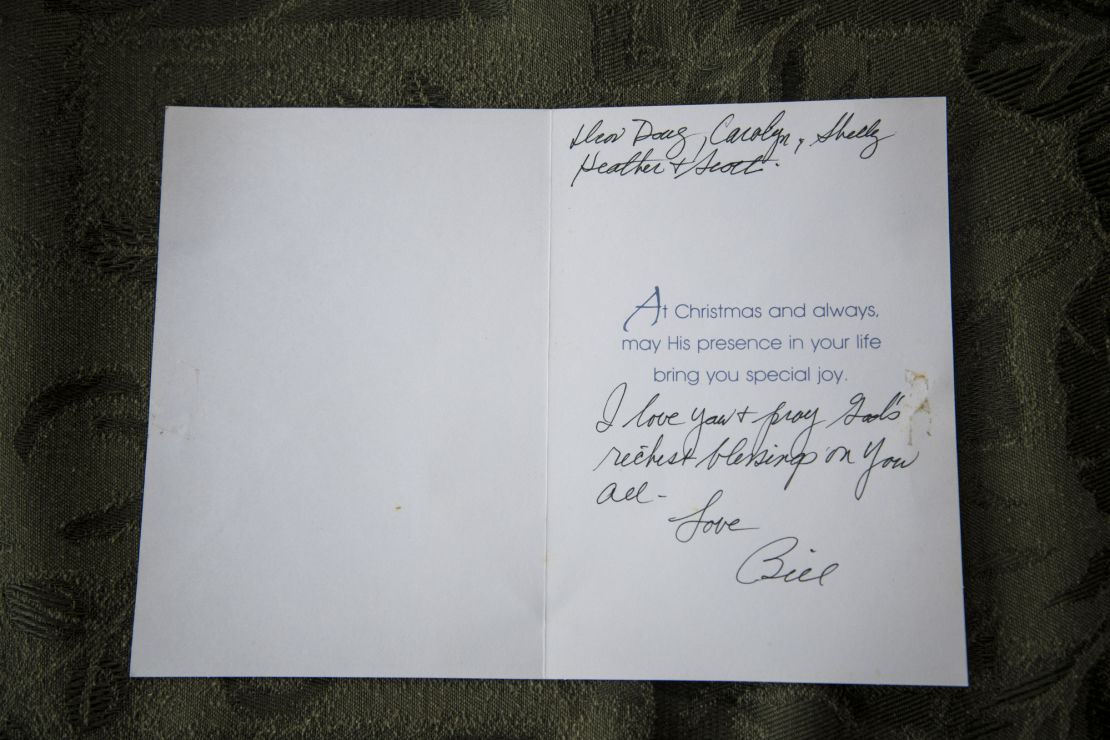

When their daughter’s teacher told them he was having marital problems, they responded with compassion, inviting him for meals and visits. Murdock spoke with them about God, attended Bible study in their home and played Christian songs on his guitar. And he spent more and more time around Shelley, who said she had become convinced they were in love.

Gaile and Ed Peavler came by the Loves’ home to worship and noticed a closeness between Shelley and her teacher that they found worrisome.

“I remember them sitting on the floor together, the looks passing between them, I just knew there wasn’t something right there,” Gaile Peavler recalls. “She just had a big crush on him, and he was encouraging that…. Their behavior, to me, was just like a couple that were flirting with each other and sharing secrets.”

By this time, Shelley said, Murdock was stoking a fantasy in her imagination late at night in phone calls after her parents went to sleep.

“I didn’t speak very much. I mean, he mostly wanted me to be quiet, ‘cause he didn’t want me to be caught.” She said Murdock told her they would get married when she turned 16 in a state where it was legal. He described dates they would go on, she said, and the children they would bring into the world and name Clayton Joseph and Rebecca Lee.

“This was night after night after night….I had gone from hating him…to now I’m totally, utterly dependent.”

Shelley felt that her teacher, who was now 31, had isolated her from her peers. She and Murdock, she said, were engaging in masturbation and oral sex.

Shelley shared a bedroom with her 11-year-old sister Heather, who remembers Shelley tucked under her desk late at night, ear pressed to the phone. She and her brother, Scott, who was 12, also remember Murdock being at their home when their parents were away and insisting that they leave him and Shelley alone, sometimes in a bedroom.

“The door would always be shut,” recalled Scott. “It was always some private project. It was like, ‘Oh, no, no, you guys need to stay out here. This is top secret.’”

They said Murdock would tell them the two were working on special presents for them – for Christmas, or their birthdays.

In tears, Heather recounted Murdock sending her to their dark, dirt-floor basement. “He would shut the door behind me,” she said. “I remember being able to hear my sister and Bill. They sounded playful, they sounded in love.

“It certainly didn’t feel like it was about a Christmas present or a birthday present,” she continued. “I began to feel like I had to protect my sister, that I had to figure out what was going on…I had to expose him for who he really was to my parents.”

Heather thought she had the proof she needed when she witnessed Murdock kissing her sister on the lips. She immediately told her mother.

Carolyn confronted Murdock.

He told her that Heather got it wrong; Shelley was upset, and he was consoling her with a simple kiss on the cheek. Carolyn believed him.

“There was just a really good story behind it, and Shelley backed him up,” Carolyn recalled.

But she couldn’t help but worry. “Sometimes, I’d come home from work, and he would be there. But he would always tell me he just got there….And I was always careful to tell him, ‘Don’t be here when I’m not here.’”

Scott remembers playing in the woods near their house and seeing Murdock pick Shelley up or drop her off on a road around the bend from their home.

“I definitely remember him coming up and not actually driving all the way to our house, which I always thought was weird as a kid,” he said.

Shelley told CNN that in the midst of the sexual abuse, she told her parents that men in a van took her into the woods but she escaped unharmed. The couple said they reported the incident to authorities and soon after, Shelley admitted she’d made it up.

Carolyn recalls the detective warning them that someone might be abusing Shelley and the story was her cry for help. It’s a scenario generally supported by child psychologists. Children who are being sexually abused, they say, sometimes invent stories as a way to alert adults without disclosing the real source of their pain.

“This was happening, and it was hurting,” Shelley says now. “It just wasn’t happening with the guys in the van.”

The false report and Shelley’s increasingly withdrawn demeanor deepened her mother’s suspicion of Murdock. One day, Carolyn sat on a hilly area overlooking the road to their home, watching for Murdock’s car. She saw him drop Shelley off away from the house.

Murdock arrived at the home first, Carolyn said, and Shelley walked slowly behind him to appear as though they’d traveled separately.

“I walked in there, got their alibi, got their story, which was completely false and I knew it,” Carolyn said. “And I tore into him and told him never ever be in our house again.”

The Loves believed they were done with Murdock. A short time later, they received a note from his wife Dana, thanking them for the kindness they’d shown her husband. The couple had reunited.

Carolyn and Doug thought nothing of it.

Shelley was devastated. That night, she said, she walked to a nearby bridge and contemplated jumping.

“We wouldn’t have known why, if she had done it,” her father said, weeping at the memory.

Shelley’s grades plummeted, and she refused to return to Erwin High. Her parents enrolled her in a private school. One of her new friends, Michael Hayes, sensed right away that something deeply bothered her. He gently asked what was wrong.

“She told me that she had been having sex with her teacher,” he told CNN. “I told her, ‘You have to tell your parents. You have to tell them.’”

Emboldened, she did.

Doug Love was livid. He wanted answers. He confronted Murdock in a school parking lot in February 1988 and recorded the conversation. Murdock declined to hear the entire recording but listened to parts of it and confirmed it was authentic.

The father asked Murdock if he had “a physical relationship” with Shelley.

“Oh no. No, no,” Murdock said.

“You’re denying that?” Doug asked.

“I mean, outside of a hug, you know, she’d hug me and stuff like that,” Murdock replied.

“She’s told us more than that, Bill. She’s told us more than that, Bill. She’s told me about, about your having her masturbate her (sic). And, and she’s told Carolyn that.”

“No,” he said.

“And not only once but numerous times, Bill.”

“No sir, no sir.”

The father pressed on. “This girl has been an emotional wreck. She’s had counseling. She’s had a hard time. She, she’s never had any type of a sexual relationship, hasn’t even dated before. And then she comes up with this, and she’s having a heck of a hard time with it all, Bill.”

Murdock continued his denial but said, “I’m not calling her a liar… Her emotions and probably mine are getting a little bit out of hand.”

He brought up Shelley’s false report about the men in the van, said he talked to her about “trouble” with a boy. “And I tried to help. And I’m not a threat to anybody.”

He apologized and said he might have made mistakes.

“If I did, like I said, I’m very sorry and I never meant for it to happen and all I can do is ask your forgiveness.”

He said he “broke it off” because “the whole thing was wrong. Emotions that were building up and stuff like that was wrong.”

He offered twice to resign his teaching job and nervously asked, “What are you planning to do?”

“I’m not sure, Bill.”

In his interview with CNN, Murdock denied some allegations and said he could not recall other scenarios the Loves described.

He did remember the conversation with Doug Love. He said he did not know it had been recorded but confirmed it was his voice on the tape.

“I think I probably asked his forgiveness,” he told reporters, “just because if, if he thought there was anything inappropriate and if emotions were getting out of hand, it was about the whole family. And thinking that, you know, if, if he, if this is going to be a big thing and, you know, all of this, you know, I mean, it’d be just as easy to, to resign.”

In the conversation with Doug, Murdock never mentioned accusations he has repeated over the years: that Carolyn Love made up the abuse because he rejected her advances.

He acknowledged being at the Loves’ home during Shelley’s freshman year. “We were close, at their invitation, I mean, we were, we were certainly friends during that time.”

He said the family became incensed when he reunited with his wife. “They weren’t happy about the fact that we were getting back together….They just said they didn’t feel it was the right thing to do and they were, they felt that, you know, that God didn’t want us to, to get back together… They, I guess, thought I was more part of their family. And again, they wanted, you know, me to, you know, to stay.”

Murdock acknowledged to CNN that he drove Shelley home from the football game but said he didn’t kiss her. He denied putting Heather in the basement, late-night phone calls with Shelley and conversations about marriage and children.

He denied touching her in class in middle school, giving her his clothes to wear or coming by the house suggesting that she be his soccer team statistician. He couldn’t remember being in the house with Shelley when her parents weren’t home or the confrontation with Carolyn after Heather said she saw them kissing.

He said he only dropped Shelley off away from her house once.

“One time she was walking down the road, you know, and fairly far away,” he said. “And so I picked her up, and she said, ‘Well, why don’t you just drop me off here?’”

And he said it wasn’t Carolyn’s accusations that made him stop visiting.

“I felt it was time to stop coming around the house, being uncomfortable Dana and I were getting back together,” he said. “And, you know, those– it just wasn’t– you know, you know, it was, was not good for, for the marriage, not good for, for Dana and I.”

Murdock said Doug and Carolyn Love suggested being the couple’s marriage counselors but declined to explain why they would make such an offer if they were unhappy that the Murdocks had reunited.

The Loves and Murdock agree there was a confrontation at his apartment. It occurred after the recorded encounter. Both Dana and Shelley were there. Murdock again denied abusing the girl and told CNN his wife believed him.

The Loves say Dana later called and asked to meet with Carolyn. Dana wanted to know, Was the couple planning to go to authorities? Carolyn said they were.

Would they be willing to meet with Dana’s friend in the Buncombe County District Attorney’s Office? Yes, the Loves said.

They felt sorry for Dana, who suffered from cystic fibrosis, and didn’t think prison was the answer for Murdock but wanted him to pay some price and get counseling.

Dana’s friend, Assistant District Attorney Bert Neal, recalled meeting with the Loves and their teenage daughter. He found Shelley “totally credible,” he told CNN.

“She was a normal little girl, and it was a good family,” Neal said. “And I just didn’t see that things would be made up.”

As Neal recalls, he worked on the case initially but his boss, District Attorney Bob Fisher, took it over. Fisher is dead, as is the judge. Because the case is so old, the District Attorney and Buncombe County Sheriff’s Office said they no longer have records.

Neal said that Dana, who he would represent in her divorce in 1992, told him “she could easily believe the accusations.”

Her second husband, journalist Keith Jarrett, told CNN that Dana had been disturbed by the attention Murdock showed Shelley and “came to believe he was guilty.” Dana died in 2000.

The Loves wanted Murdock prosecuted but were unwilling to allow their emotionally fragile daughter to testify in court. Carolyn and Shelley said they were interviewed by a sheriff’s investigator.

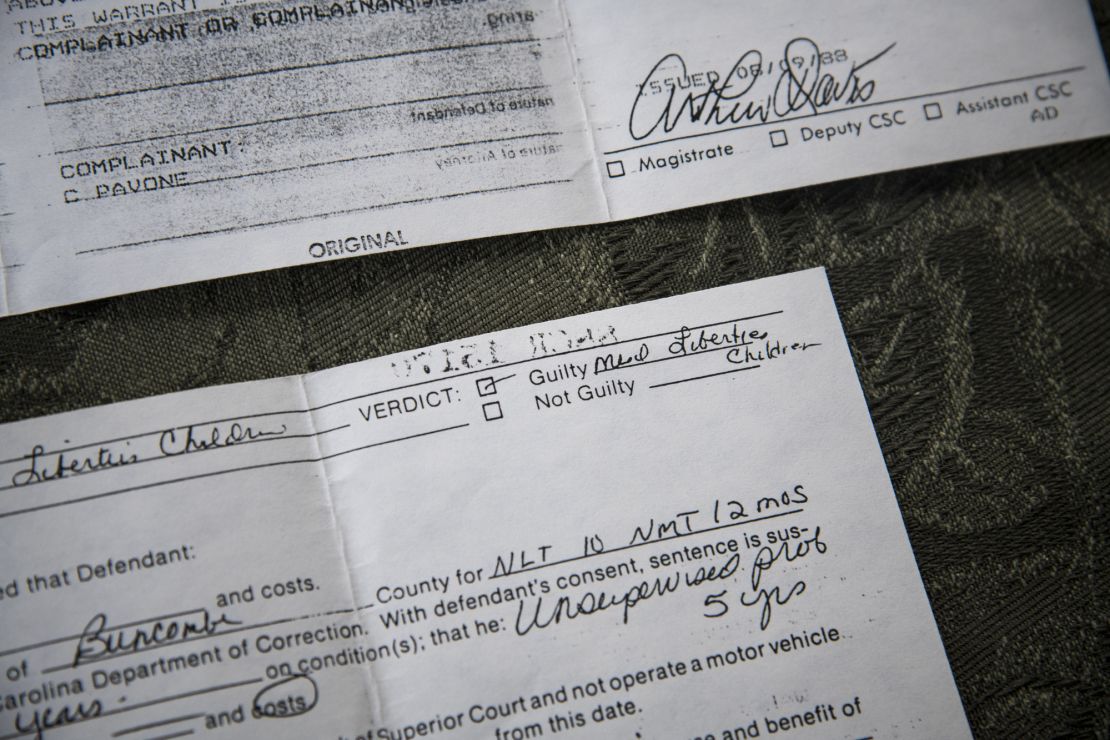

On August 9, 1988, a warrant was issued for Murdock’s arrest for felony indecent liberties with children – taking “immoral, improper and indecent liberties with Shelly (sic) Love” and committing a “lewd and lascivious act” on her. He immediately resigned from Erwin High.

Sixteen days later, Murdock pleaded guilty to what is listed on the official court record as “misdemeanor liberties with children.”

A law professor and three former Buncombe County assistant district attorneys called the quick disposition highly unusual for such a case, which normally would take months or years to resolve. Even more unusual was the charge, misdemeanor liberties with children.

There was no such charge, Neal and other legal experts told CNN.

“It appears that they just decided to call a felony offense a misdemeanor. How you get there from here, I have no idea,” said Rebecca Knight, a former Buncombe County sex crimes prosecutor and retired district court judge.

Fisher arranged the plea agreement, said Neal, who was censured by the State Bar in 2006 for missing court appearances and had his license inactivated in 2012 because of a disability. Murdock spent no time in jail and received unsupervised probation. He was ordered to “remain in counseling until such time that [the] counseling agency feels he has rec’d maximum benefit.”

Murdock had been seeing a marriage therapist for four months by then, according to the therapist’s notes, because of “accusations by a high school student of sexual impropriety and ensuing marital problems.” He continued seeing her for his court-ordered treatment. She observed him to be “a 33 year old attractive male who was neatly dressed and well-mannered.” He’d been a “model citizen,” she wrote, and she commended his “problem-solving techniques.”

The therapist determined that Murdock “does not fit the personality profile of a sexual abuser.” A little more than two months after his conviction, she concluded the treatment was no longer necessary.

Neal now says he thinks Murdock got off light. “I don’t agree with the disposition,” he said. “I thought he should have paid more of a price than he did.”

So do the Loves. They said they were unaware of the plea deal and learned of it in court.

Asked what misdemeanor charge he pleaded to, Murdock told CNN, “I’m not even sure what, what, what it was.”

He said he wasn’t questioned by law enforcement. Shelley’s siblings said they were never interviewed either.

Murdock said his attorney, Brent O’Conner, advised him to plead guilty. “He said that, first of all, it would cost about $20,000 to defend,” he said. “And even though he knew it wasn’t true, he said, ‘How do you prove a negative? How do you prove that you didn’t do something?’”

O’Conner did not respond to numerous requests for comment. But he has written a letter in defense of Murdock, which one former Eblen board member read to Wiley Cash during a telephone call last year. In the letter, according to Cash’s notes, O’Conner said Murdock vehemently denied the allegations and shared none of the traits of the sex offenders he’d represented.

The Loves, disappointed in the outcome of his criminal charge, left Asheville. “We moved away…specifically to get [Shelley] out of here and to get our family back on track,” Carolyn said.

A few years later, while watching Scott compete in a state wrestling match, the Loves were stunned to see the coach of an opposing team: Bill Murdock, a new employee at Asheville High School.

Carolyn said she and Shelley then drove two hours to the school and shared their story with administrators. Murdock resigned on March 30, 1992. He told CNN he had been hired as a temporary teacher.

“This had come up again,” he said. “I just decided that…this isn’t worth going through all of this again.”

Outraged that Murdock had been allowed to continue teaching, the Loves contacted the District Attorney and the school superintendent at the time, according to documents CNN obtained. An attorney for the school district concluded that Murdock’s conviction was grounds for his educational license to be revoked but that since he was no longer teaching and because of “the passage of time,” no action would be taken.

At a minimum, the Loves had wanted Murdock to receive sex offender treatment and be barred from working with children. They got neither.

The birth of a charity – and an image

During the time the Loves say Murdock abused their daughter, he taught gifted middle school students at Super Saturday, a program on the campus of the University of North Carolina at Asheville, according to job applications he submitted to UNCA. He taught there through 2001. A statement by the university said background checks were not required until after Murdock left.

Murdock’s job at Eblen Charities puts him in regular contact with low-income children and families. The board has known about his conviction for years and stood by him.

“This thing has been gone over so many times,” said Dewey Andrew, a board member who has been involved with the charity since the beginning.

He said he did not know the details of the case. “I know what I’ve heard and what his attorney has said and all those kind of things. So I think that the, the, whatever it is that someone’s bringing up is a bunch of bull.”

“I will take up for Mr. Murdock to the very end,” Andrew said before abruptly ending the interview.

Lou Bissette, a former Asheville mayor and ex-Eblen board member, said that after he left the charity several years ago “the board or the chairperson looked at it, looked at all that they could find, and, and determined that there was not enough evidence there to do anything about it.”

Bissette said he’s known Murdock more than 20 years and never heard of any other allegations, noting that “he’s had access to hundreds of children and families, thousands over the years….I think what Eblen has done has been really incredible for our community.”

A statement by the Eblen board, released last week to Asheville media outlets, said it had long been aware of “an allegation” in Murdock’s past, investigated it and “determined that no further action was necessary.”

“We believe in helping people and giving people a second chance,” the statement said. “Bill has proven himself worthy of continued employment as our executive director. He has done good work here and has improved the lives of the people of western North Carolina. We continue to stand in support of Bill Murdock.”

It’s unclear who wrote the statement or whether it represented a consensus of the board. Two board members declined to answer questions, and others did not return messages seeking comment.

The genesis of Eblen Charities was a 1990 golf tournament Murdock helped conceive to benefit a foundation for cystic fibrosis, according to Eblen’s web site and Murdock’s writings. Murdock and his co-organizers needed a sponsor and approached Joe Eblen, who ran the family-owned Biltmore Oil Co., a wholesale gasoline supplier and operator of retail convenience stores.

A wrestling aficionado since elementary school, Murdock recruited professional wrestlers and the tournament became an annual event. In 1991, the family of a young girl with cystic fibrosis needed help paying for transportation to take their daughter for treatment at Duke University. The parents worked and did not qualify for financial assistance.

“I called Joe and he, out of his own pocket, paid for the family to go, and then we decided, you know, there’s needs in our community,” Murdock told CNN. “I had a yard sale. We raised $400 and we started Eblen.”

Murdock, who had been working at a real estate company, became its first employee, initially working out of Biltmore Oil. The charity stood apart from other aid organizations, offering assistance without rigid guidelines.

“Everything went through him,” said Leslie Anderson, an Asheville-based consultant to nonprofits. “I remember him standing up at any number of meetings and saying, ‘Here’s my phone number. All you need to do is call me and I will make it all happen.’”

Eblen Charities went on to contract with the county government, disbursing money for heating and utility assistance and overdue bills for rent, power, gas and water. Local businesses helped provide turkey dinners at Thanksgiving, back-to-school supplies, and shoes and clothing for needy students. The annual budget grew to $5 million, according to its 2016 financial statement, the most recent available.

To Joe Eblen, Murdock was “like a son,” Anderson said. Raised by grandparents, Murdock said his own father had little presence in his life and his mother died when he was a toddler.

Joe Eblen died in 2013. The Eblen family declined to comment for this story.

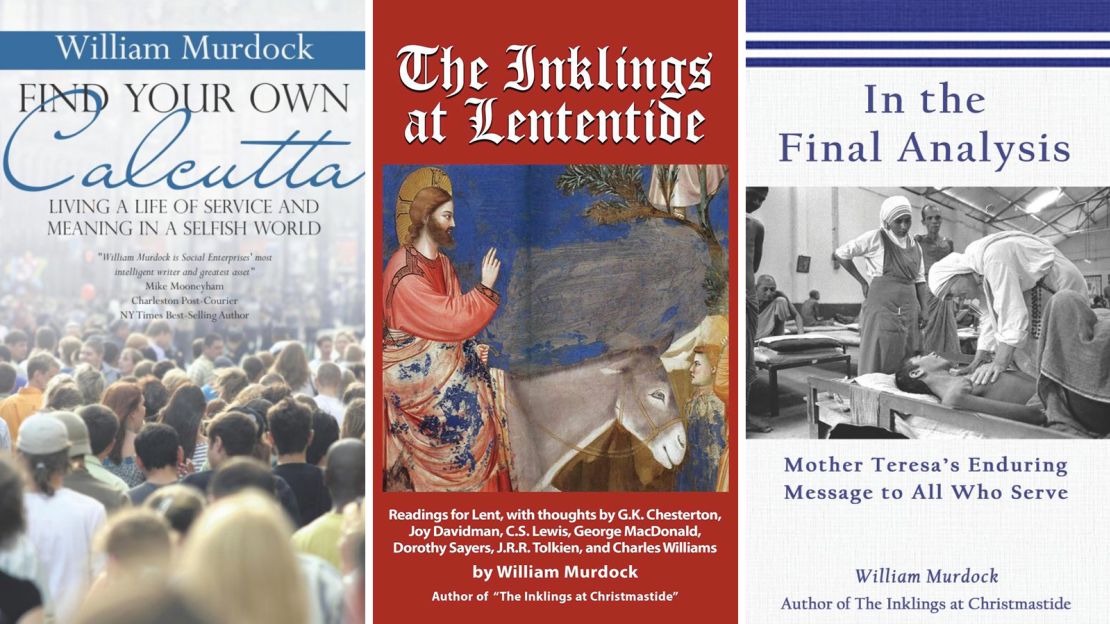

As the charity grew, so too did Murdock’s renown. He became its public face, garnering positive news coverage and penning books and op-ed pieces that read like Sunday sermons.

“We all would do well to follow Mother Teresa’s example and not only see the need but to act without delay,” he wrote in his book “Find Your Own Calcutta: Living a Life of Service and Meaning in a Selfish World.” A framed letter from Mother Teresa, one of a half dozen he said he received after finding her address in Parade magazine, hangs in his office.

“I think some people think of him as, you know, Mr. Do Good or Do Great, almost saintly,” Anderson said

Murdock lives in a $1.1 million, 4,500-square-foot house in an exclusive neighborhood. The land, he said, was given to him by Joe Eblen. “We were able to, to build the house for a lot less than we were able to buy one,” Murdock told CNN. He said he makes $65,000 a year and has turned down raises.

The charity’s increasing visibility earned Murdock a seat on the boards of numerous organizations, including Children First, a nonprofit Anderson helped found to advocate for children. Background checks were not required for nonprofit boards, she said.

In 2001, Murdock summoned three Eblen employees to a meeting, concerned that his criminal history might become public, according to two of the attendees.

“He said, ‘I need for you to know my side,’” recalled Liz Robinson, who said she worked for Eblen for 17 years. “The mother of [Shelley Love], and this is his story, wanted to sleep with him and he refused…. She said, ‘If you don’t have an affair with me, I’m going to tell everybody you violated [Shelley].’ I remember asking him, ‘Why would a mother do that to her daughter?’”

Karen Brinson Bell recalled Murdock saying he “had been taken in by this family when he and his wife were having marriage problems…When the wife or mother made advances and he rejected her, she then accused him of being inappropriate with the daughter.”

Brinson Bell didn’t believe him. “I went home, told my husband, and said, ‘I’m done.’”

She said she left the charity several months later.

Dubious awards and exaggerations

Murdock continued to polish his public persona, adding to his resume dubious honors that were readily accepted by university boards and reported in the local media.

At the UNCA graduation last May, the interim chancellor introduced Murdock, the commencement speaker, as a recipient of the Mother Teresa Prize for Global Peace and Leadership. The award was given by the Luminary Leadership Network, a limited liability company created by Murdock using his home address, CNN discovered.

An Eblen Charities announcement said “laureates” were selected by a committee led by inspirational speaker Jamie Minton of Atlanta and Heath Shuler, a former Congressman, Eblen board member and long-time Murdock supporter.

Shuler introduced a 2007 tribute to Murdock in Congress, calling him “a most distinguished constituent,” and is quoted on Murdock’s author website as saying “Murdock is the essence of affection without limitations.” Shuler did not respond to messages seeking comment.

Minton said he created the Luminary Leadership Network with Murdock to host “Lead through Change,” a 2014 event in Asheville that featured speakers including Shuler and John Maxwell, a self-described leadership expert.

Minton said he’d known Murdock for years and admired the charity’s work. “I wanted to, wanted to honor Eblen, honor Bill,” he said. Maxwell also received the Mother Teresa award. It was the only year the prize was given.

Even though the award came from his own company, Murdock told CNN he was surprised to receive it. He acknowledged the prize was not affiliated with Mother Teresa. “But there’s a lot, there’s quite a number of awards in Mother’s name that aren’t affiliated.”

Eblen’s website and Murdock’s book covers and bio claim the Eblen Children’s Pharmacy won the Peter F. Drucker Award in 2001 for being “the most innovative nonprofit program in the country.”

Laura Roach, who administers the prize, told CNN she could find no record of Eblen winning.

“There were some years during the prize or award where there were runners up and second or third place,” she said. “But I can tell you that it is inaccurate for him to say on his website that his organization was the most innovative program in America.”

Murdock told reporters he had an email “and some correspondence from them at the time…. I’ll have to dig it up.” He has yet to produce the documents.

In his book bios, Murdock exaggerates his educational background, saying he was “educated at Asheville-Buncombe Technical Community College, Mars Hill College, Duke, Harvard and Stanford Universities.” He is a graduate of the community college and Mars Hill University, a private liberal arts school near Asheville. He completed one-week courses in non-profit management at Harvard and Stanford and a 50-hour program at Duke, spokespersons said.

Murdock said he did not think his claim was misleading.

“I don’t think so. I think it might be misinterpreted and actually– I’ll make sure those are, are deleted ‘cause, you know, I certainly didn’t want to, you know, mislead anyone….”

Murdock’s credentials impressed three Asheville-area institutions of higher learning and the county school system.

Mars Hill appointed Murdock to its board in 2017. Shortly after the appointment, a university employee who was the sheriff’s investigator in Murdock’s 1988 case alerted her supervisor, Laura Whitaker-Lea, to his conviction. Whitaker-Lea, now at a college in Georgia, told CNN she went to the Mars Hill president, and a short time later, Murdock resigned.

Mars Hill did not respond to questions. Murdock told reporters he left because he was too busy.

Buncombe County schools in 2016 appointed Murdock to the board of his alma mater, the Asheville-Buncombe Technical Community College, where he had also served on the foundation and been a commencement speaker. The school district declined to answer questions about the appointment or its December dedication in Murdock’s name of a library at Community High School. Superintendent Tony Baldwin serves on the Eblen Charities board, according to the charity’s web site. He did not respond to requests for an interview.

An A-B Tech spokeswoman said college administrators, including President Dennis King, did not know of Murdock’s criminal record. But a foundation board member told CNN she informed King more than a year ago. He declined to be interviewed, and a statement from the college said the board plays no role in appointments, which are made by the governor, county commission and local school boards. Contacted by CNN, four board members who were unaware of Murdock’s conviction said they were alarmed to learn of it.

Board member Jacquelyn Hallum said the school district should look into revoking his appointment.

Brinson Bell, the former Eblen employee, thought she could stop her alma-mater, UNCA, from bestowing an honorary degree upon Murdock. She spoke to the chancellor’s chief of staff. “She said, ‘Can I ask you some questions so I have notes to turn over for our investigation?’” Brinson Bell recalled. “The next time they were back in touch with me, I think was about a week. They’d already done their investigation, and they were going to move forward. I was speechless.”

So was Wiley Cash, the writer-in-residence at UNCA. He learned of Murdock’s background six months after then interim Chancellor Joe Urgo introduced Murdock to the May 2018 graduating class as a “visionary” and “community leader.”

Fearing UNCA had made “an egregious error,” Cash began a series of phone calls to top university officials. He took detailed notes, which he shared with CNN.

The notes show that Urgo told Cash, “rescinding the invitation after making the announcement would be a shitshow. We thought it was best to believe that he was telling the truth and that nothing else would come to light.”

Urgo did not return messages seeking comment.

Cash said the chairman of the UNCA Board of Trustees, Kennon Briggs, told him Murdock was chosen for his “body of work” and that “all of us misstep,” but his service to the poor outweighed an old conviction. Briggs mentioned the Mother Teresa and Drucker awards and said the university had interviewed Lou Bissette and Dewey Andrew.

“Both of those people had served on Eblen’s board,” Cash said. “I knew the investigation couldn’t have been too thorough.”

Briggs did not respond to requests for comment.

Cash said he has asked the acting university provost to rescind Murdock’s degree three times since November. The board did so in an emergency meeting this month, after CNN outlined its findings.

Murdock voluntarily handed in his degree before the meeting, but the board still voted to rescind it.

UNCA said in a statement that honorary degrees are “based on lifetime achievements” and that the board confirmed Murdock after Urgo twice spoke to him about the 1988 case. The current chancellor is now reviewing the honorary degree selection process, the statement said, and is considering “full background checks” on candidates.

Cash believes the reckoning has been a long time coming.

He asks how Asheville – “a small southern town that is known as one of the most progressive in the Southeast” – could also be a place where a crime against a child is “buried, overlooked, willfully ignored and ultimately uncovered after 30 years.”

“My story is important”

Murdock’s abuse of Shelley, her father said, was as if someone set off a bomb in the family. Each member bares shrapnel wounds.

“It’s the biggest regret we have had in our lives,” Doug said.

Looking back, he sees Murdock “as a wolf in sheep’s clothing…coming into my family under the guise of friendship and fellowship.”

He and Carolyn’s marriage has weathered years of strain from the guilt they carry.

“How could have this have happened to us? How could we have been fooled? How could we have been so stupid? How could we have been so naive?” he said. “If you’re a caring, loving parent you’re going to ask yourselves those questions and many, many more.”

For years, Carolyn focused on keeping her suicidal daughter alive, leaving less time for Scott and Heather. “They lost their mom and dad at that point,” she said.

Learning from CNN that Murdock put the blame for his charge on her, calling her a scorned woman, infuriated Carolyn.

“That is absolutely not true,” she said.

“It was nothing romantic. It was nothing but friendship, and he wanted a close friendship, and we allowed that to happen.”

The Loves had roots in Asheville, and one by one they returned. Shelley married Mark Baldwin and came back so the couple could help care for his mother. Doug and Carolyn soon followed.

Only Heather stayed away. She has journaled for years, at times writing about her memories of Murdock as a symbol of darkness and loss of innocence. In an argument with her husband last year, she said she inadvertently blurted out: “Don’t put me in the basement.”

For Scott Love, whose job is to care for children, the present is a reminder of the past. He has treated kids of ardent Murdock supporters and remained silent about his family’s experience.

“I’ve always felt like I’ve had to walk a tightrope with that,” he said

Shelley felt she couldn’t escape Murdock.

“I’ve watched him enjoy a whole lot of success in the community, and it’s hard,” she said.

“There would be times I would hear his voice come on the radio. I would see his face on the news, and I would just start to shake from head to toe.”

Dr. David Rogers, a general practitioner, diagnosed Shelley with panic attacks in her 30s, suspecting she had been abused, he told CNN. He said she was defensive, untrusting and “very fragile.” She told him about Murdock, and he said he found her credible. He referred her to psychologist Judith Pohl.

When Pohl began treating Shelley in 2006, she was severely depressed, anxious and exhibiting symptoms of PTSD, Pohl said. Shelley told Pohl, and later CNN, that she has been sexually assaulted by others in her life, but never reported those incidents. Pohl noted that victims who are abused once are often violated again.

“Shelley has been consistent in the way she has described her abuse and trauma,” Pohl said, speaking to CNN with Shelley’s permission. “I have absolutely no reason to ever question or doubt anything that she said.”

Shelley resigned herself to accepting that her story would never be heard. But when reporters asked, a sense of relief rushed over her and her family. They wanted to speak, they said, not just for themselves but for the community, for anyone who assumes that abuse could not happen in their own families, for those who choose to disbelieve and look away.

“This is the day we want to say, ‘It ends. It ends here. Here is our story,’” Doug said, his voice cracking. “People can choose to believe it as they see it and hear it or they can choose not to.”

“And it’s got to resound with some other people out there. And they’re going to say, ‘Yeah, Mr. Love was fooled. His family was fooled. ‘I hope to God our family wouldn’t be fooled like this,’ they might say to themselves, ‘but maybe we could have been.’”

The Love family believes Eblen Charities does good and important work and should continue. They just want Asheville to see the Bill Murdock they knew.

“I don’t feel vengeful toward him,” Shelley said. “But I feel like the truth is important. And I feel like my story is important. And I feel like people don’t know who he truly is.”

Sally Kestin is a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist living in Asheville. Ashley Fantz is a senior investigative reporter at CNN who focuses on crime, military issues and gender violence. They can be reached at kestinsally@gmail.com and Ashley.Fantz@turner.com.