When a Missouri TV station asked Republican Rep. Todd Akin in 2012 about his view on abortion in cases of rape, his answer was widely viewed as a disaster. “From what I understand from doctors, it’s really rare,” the Senate candidate said confidently. “If it’s a legitimate rape, the female body has ways to try to shut the whole thing down.” Conservatives from Mitt Romney to Sean Hannity quickly said he should step aside. Akin’s campaign funds dried up. He eventually lost the election by more than 15 points.

For some anti-abortion activists, Akin’s blunder was a wake-up call. To them, the problem wasn’t that Akin was wrong to suggest that anti-abortion policies didn’t need to include exceptions for women who had become pregnant by rape. It was that his explanation was medically nonsensical and distracting. “We’re going to re-look at how we endorse and train candidates,” the president of the Susan B. Anthony List, Marjorie Dannenfelser, said in a speech the day after the election. “From now on, they will not be sent in the field with our support without knowing how to actually discuss the issue with compassion and love, and to exploit the other candidate’s extremes.”

Seven years is an eternity when it comes to abortion policy in America. On Wednesday, Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey signed a historically restrictive anti-abortion bill that would effectively ban the procedure from the moment of conception. Hours later, Missouri’s state Senate passed a bill effectively banning the procedure at eight weeks of pregnancy. Perhaps even more startling to many casual observers: The legislation in both states does not allow exceptions for pregnancies that result from rape or incest.

Historically, mainstream anti-abortion activists and politicians have made allowances for pregnancies conceived from rape or incest, on the grounds that it would be cruel to force trauma victims to endure pregnancy and birth. A major evangelical report on contraception and abortion in 1969 recommended allowing abortion in such cases, observing the consensus that “subjection of the innocent party to such suffering by withholding the opportunity of an abortion is unwarranted.” In a 1975 radio address, Ronald Reagan said that abortion was “the taking of a human life,” but also that having an abortion after rape was an act of self-defense, and that a woman has the right to “rid herself of a child or refuse to have a child resulting from rape.” Billy Graham openly endorsed such exceptions; George H.W. Bush and his son did, too. Donald Trump said during his presidential campaign in 2015 that he was “for the exceptions.”

That was then. Alabama’s decision to omit exceptions (other than when the mother’s life is at serious risk) is partly because the law’s proponents wanted a “clean” bill to directly challenge Roe v. Wade in the court system. But it is also a reflection of the coalescing consensus in contemporary anti-abortion circles that rape and incest exceptions are morally unacceptable.

“For many traditional pro-life groups, this is now a litmus test for your seriousness about being in favor of the prenatal child,” said anti-abortion ethicist Charles Camosy, the author of a new book on the connections between abortion and issues including immigration and mass incarceration. “Lost is any sense of complexity about the actual arguments, much to the detriment of the movement both intellectually and politically.”

The punitive logic of exceptions has never pleased pro-choice advocates. The implication is that only “innocent” women should be free to make decisions about their pregnancies, while women who made the choice to have sex should not. “There’s definitely a problem with the idea that there are good abortions and bad abortions, and good girls and bad girls,” said Alexa Kolbi-Molinas, a senior staff attorney with the ACLU Reproductive Freedom Project. “That can be manifested in allowing only limited exceptions for what some might feel are ‘good abortions.’ ” Kolbi-Molinas said the functional difference between a near-total ban with rape and incest exceptions and without is almost nonexistent. But exceptions do make even strict anti-abortion laws more palatable to the many voters with complex views on the issue. More than three-quarters of Americans believe that abortion should be legal in the first trimester in cases of rape or incest, according to a 2018 Gallup poll.

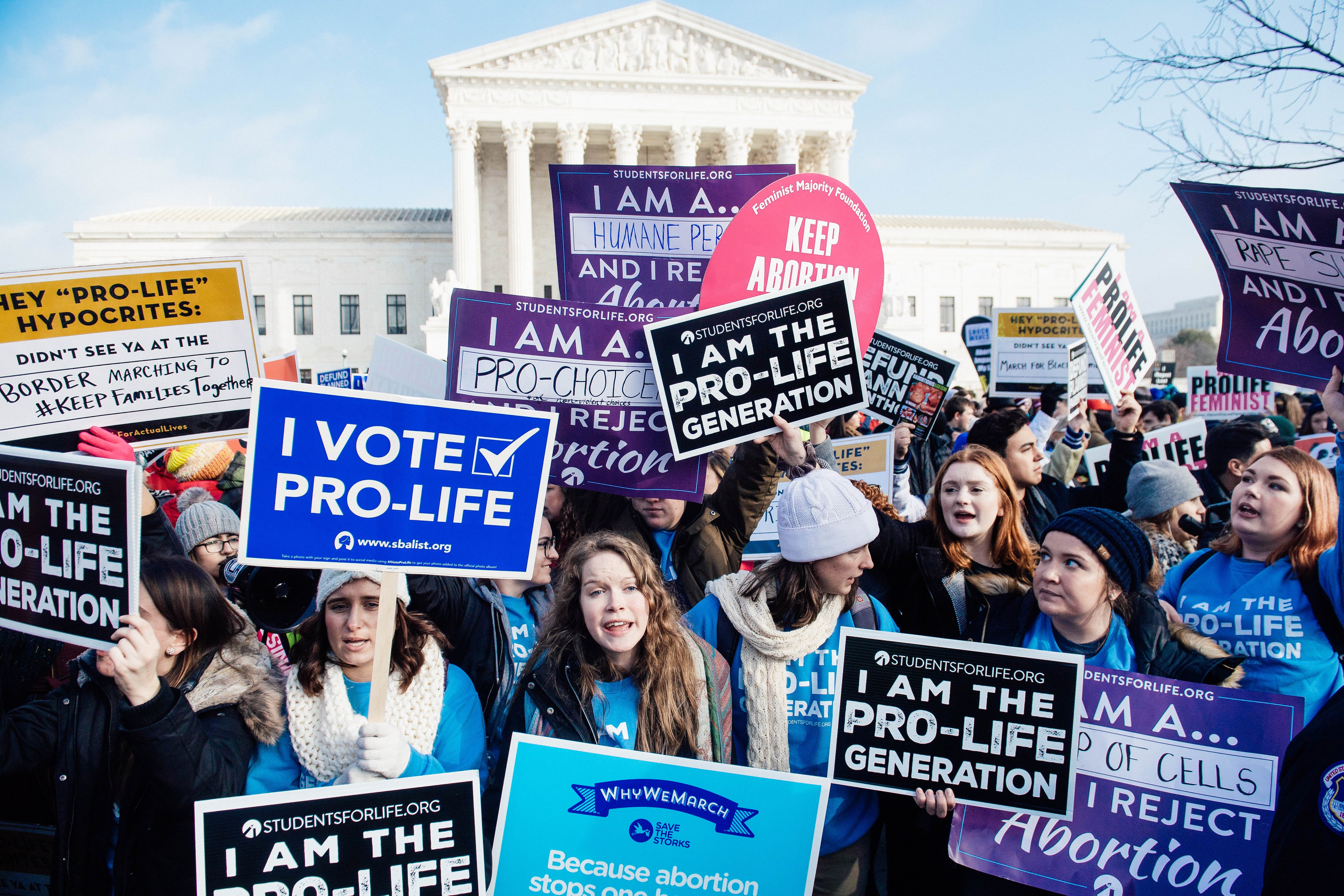

The mainstream anti-abortion groups that now argue against exceptions make a simple claim: If even the earliest abortion is murder, then surely such exceptions are morally unreasonable. As the president of Students for Life of America, Kristan Hawkins, put it on Wednesday: “If my father would commit a sexual assault tonight, would the survivor of that horrific assault be justified in killing me? No, of course not. So what’s the difference?” Hawkins wrote a blog post after Todd Akin’s 2012 comments about her evolution toward this view. In 2014, Students for Life launched a “We Care” tour of college campuses, with the goal of equipping student activists with talking points to answer questions about why rape exceptions are misguided. Several popular anti-abortion speakers and authors—including one Rick Perry credited with changing his mind on the issue—describe themselves as having been conceived in rape.

Some provocateurs now argue that disallowing exceptions is not just an uncomfortable outgrowth of a strict moral position, but an act with affirmative benefits. “Rapists love abortion because it helps them cover up their crime,” Matt Walsh wrote in a column arguing against exceptions this week. “If [a] hypothetical 15-year-old victim does have her baby, the rapist father could be conclusively proven guilty with a DNA test. But if the incestuous abuser can enlist Planned Parenthood to destroy the evidence for him, he will walk away scot-free and continue molesting his daughter for years to come.”

The conservative conversation about rape and incest began to noticeably change during the last Republican presidential primary, when evangelical favorites Ted Cruz and Marco Rubio indicated they opposed such exceptions. When other candidates questioned this—Sen. Lindsey Graham pointed out that the position is “hard to sell with young women”—the Susan B. Anthony List’s Dannenfelser rebuked them. “An attack on this aspect of these candidates’ pro-life positions is an attack on the pro-life movement as a whole,” she wrote in a stern letter to Cruz and Rubio’s rivals. “I urge you and your campaigns to reject Planned Parenthood’s talking points and instead keep the pro-life movement on offense.”

The straightforwardly triumphant reaction within anti-abortion circles to the Alabama law this week is proof that the conversation among activists, at least, has now changed decisively. The president and CEO of Americans United for Life, Catherine Glenn Foster, said in a statement Wednesday that “the violence of abortion is never the answer to the violence of rape.” Victims of child rape “need fierce advocacy & care, but abortion isn’t it,” prominent activist Lila Rose tweeted after the Alabama bill passed the state Senate. “It’s more trauma.” After a chaotic debate on the Alabama state Senate floor over an amendment that would have allowed exceptions to the law passed this week, 21 Republicans voted against it, and only four voted for it.