The following article is a written adaptation of the first episode of Thrilling Tales of Modern Capitalism, Slate’s new podcast about companies in the news and how they got there.

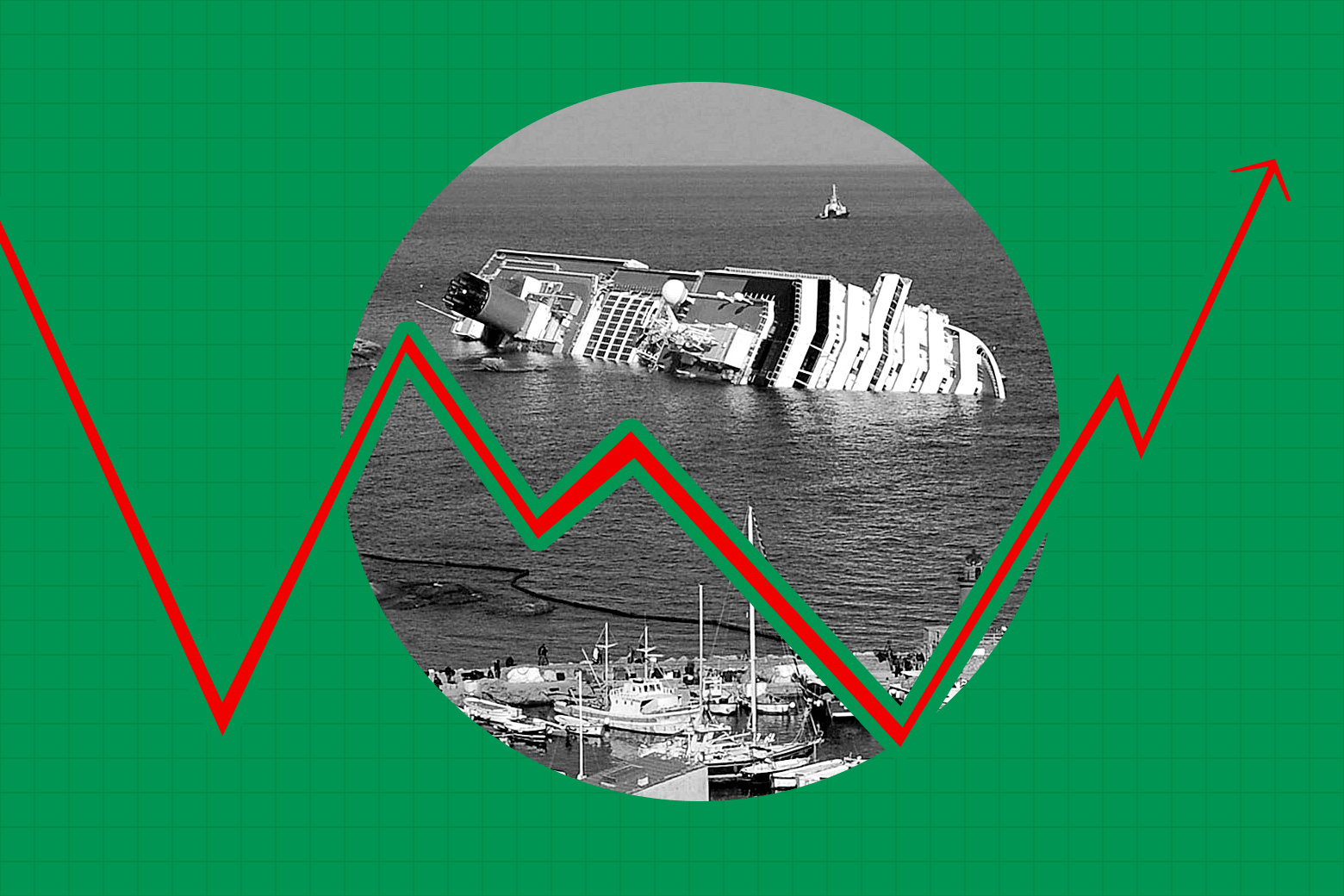

After the deadly capsizing of the Costa Concordia in 2012 and the nightmarish “poop cruise” of 2013, Carnival Corporation is once again in turbulent waters, this time because of the coronavirus crisis. Even after countries began to lock down, Carnival ships remained at sea, floating offshore, waiting for safe harbor, with no ports willing to accept them—which left crew, and in some cases passengers, stuck aboard in awful conditions. More than 1,500 people aboard Carnival ships were eventually diagnosed with the coronavirus. Dozens died, some of them on board.

The cruise ship business occupies a strange place in our collective imagination. It’s synonymous with gluttony: those obscenely large ships, and those all-you-can-eat buffets, and those armies of slovenly tourists who storm into little port towns all over the world. Cruising is also becoming known for its ugly mishaps: the poop cruises, the waves of terrifying illness. I’ve mentioned just some of the awful incidents that have occurred on Carnival ships in the last decade. They’re the ones that make big news and stick in people’s heads. But Carnival ships have also been sites of disturbing sexual assaults, and Carnival has been found guilty of a slew of environmental offenses.

It all traces back to the weird nature of the cruise industry. The Carnival Corporation is easily the biggest cruise ship company in the world. It has more than a hundred ships, which between them carry roughly half of the world’s cruise ship passengers. Its history is deeply entwined with the history of the cruise industry, and its story explains so much about cruising’s evolution.

Once upon a time, ships were basically the only way to get from one side of the ocean to the other. These ships got faster and bigger until the middle of the 20th century, when ocean liners were at their peak. In 1952 an American ship set a record by crossing the Atlantic in 3½ days, which is really fast for a ship. The problem, obviously, is that airplanes are much faster than that, and by the mid–20th century they were cheap and comfortable enough to take over. In 1958 more people crossed the Atlantic by air than by sea for the first time. Twelve years later, 96 percent of trans-Atlantic passengers were going on airplanes. The ocean liner business was essentially over, and a lot of companies were left with big empty passenger ships on their hands.

“That’s really where the growth of the cruise industry came from,” Ross Klein, a sociologist who studies the cruise ship industry, told me. “You had all of these oceangoing vessels and there was no longer a use for them. How else do you use them? Convert them to leisure, recreational, cruise ship vessels.”

Klein says the cruise ship vacation was invented for people who missed the romance of the passenger ship era and wanted to recapture it even if, instead of taking you from point A to point B, the ship just went around in a loop. One of the people who got in on the ground floor of this new cruise ship business was a man named Ted Arison, an Israeli émigré who started a company called Carnival.

Arison realized that ticket sales weren’t the only way to get people’s money. Once you had people aboard the ship, in a sort of captive situation out on the water, you could sell them copious amounts of liquor at the ship’s bars and drain their wallets at the ship’s casinos. Onboard revenue became a key to Carnival’s success.

Another key was aggressive marketing. By 1987 Carnival was the world’s most popular cruise line and was doing well enough to go public. Its initial public offering generated about $400 million. Ted Arison used that money to buy up his competition and dominate the industry. Arison died in 1999. His son Micky took over the company, and businesswise it just kept steaming along. Last year Carnival made about $20 billion in revenue. Micky Arison himself is worth more than $8 billion, and he owns the NBA’s Miami Heat.

So that’s the corporate success story. But it turns out that beneath the crystal-clear waters, there are dark undercurrents. There’s always been a kind of lawlessness out on the high seas—Carnival ships are no exception. Carnival’s main headquarters are in Miami, and the company CEO is in Miami, and its chairman owns Miami’s basketball team. But despite this overwhelming presence in a major American city, Carnival is not an American company; it’s registered in Panama. Carnival ships aren’t American either; they’re registered under various foreign flags of convenience. This strange situation, where a company that’s clearly based in the United States is not actually beholden to many of the laws of the United States, lets Carnival get away with a lot of outrageous stuff.

“Part of it goes back to the history of the cruise industry,” Ross Klein says, “which goes back to admiralty law or maritime law, where cruise ships operate on the high seas and don’t really belong to any one country. That gives them a degree of arrogance and allows things to go on that wouldn’t go on on land.”

Jim Walker, a Miami-based lawyer, has another interpretation: “It doesn’t pay U.S. income taxes. It avoids U.S. labor laws and wage laws. It underpays people from India and the Philippines. It overworks them. There aren’t any overtime laws that apply. There are no minimum wage laws that apply. So it’s an industry that is kind of above the law.”

Walker started out representing the cruise lines, but he became so disgusted by them he switched sides. His practice now exclusively sues cruise ship companies on behalf of their passengers and crew. Carnival says being on a ship is like being in a small city and that crimes can happen in any community. But if an assault happens on a cruise ship instead of on land, the victim’s legal recourse is murky. There are questions about jurisdiction, and the company has clear motivation to bury cases that might cause bad publicity.

When you have a company that is essentially based nowhere, whose operations take place on board ships roaming about in international waters, under foreign flags, all that lends itself to a certain lack of oversight, and it goes beyond violent crimes on board the ships. In 2016, Carnival was convicted of environmental offenses. It turned out that for eight years the company’s ships had been dumping oily waste into the ocean while using various tricks to avoid getting caught. The company paid a $40 million fine for that, and it was put on probation, but it kept dumping anyway. Carnival executives got hauled in front of a federal court last year after their ships were caught polluting yet again. But it seems like Carnival’s placelessness, the thing that’s allowed it to continue operating through illness and scandal, may finally be coming back to bite it.

In March, Carnival’s Grand Princess was stranded outside the San Francisco Bay for almost a week after an outbreak of COVID-19 on board. Three people died, and more than 100 tested positive for the virus. When the passengers finally disembarked in Oakland, California, the disaster became an early focal point for fears about the virus. Later reporting showed that Carnival might have mismanaged the crisis in myriad ways, even keeping cruises operating well after the danger signs about the virus were clear.

Despite this, Carnival has argued that, given the debilitating economic impact of the coronavirus shutdown on its industry, the government should step in with some kind of assistance to keep cruise ships afloat. But relief isn’t coming: The cruise industry was shut out of the giant bailout bill Congress passed.

“These companies aren’t technically American,” says Jordan Weissmann, Slate’s business and economics correspondent. “They’ve always legally operated as non-American companies. Why should American tax dollars be used to bail them out? … They got stiffed. They got entirely stiffed in a way that I wasn’t really expecting to happen but I’m glad did.”

It’s not at all clear what will happen to cruising when coronavirus fears subside. People are still, to my amazement, booking cruises for 2021. Polls say lots of people are still excited about the idea of future cruises, but some people might have a hard time ever again looking at a cruise as a fun, carefree vacation option.